Archaeological Evidence of Israel’s Forty Years in the Wilderness

"This is what archaeologists have learned from their excavations in the Land of Israel,” reported Ha’aretz magazine in 1999, “the Israelites were never in Egypt [and] did not wander in the desert.”1 One Egyptologist compared the biblical narrative of the wilderness wandering to the Arthurian legends.2 An archaeologist explained it as “memories of the stormy relationship between Egypt and the population of Canaan,” adding that “in the tenth century BCE it was ‘imported’ [and] became one of the two charter myths of the kingdom of Israel.”3

According to the Bible, after leaving Egypt, the Israelites spent many years as nomads before crossing the Jordan River to settle in Canaan. Based on chronological data derived from numerous biblical passages and counting back from the time of Solomon, the widely accepted dates for this 40-year period are approximately 1446–1406 BC.4 While the Merneptah Stele of the late 13th century BC identifies Israel as people living in Canaan, nothing is mentioned in that text about Israel’s previous history or association with Egypt.5 Is it true that the 40 years of post-Exodus wilderness wandering is a series of events for which no archaeological evidence has been found?

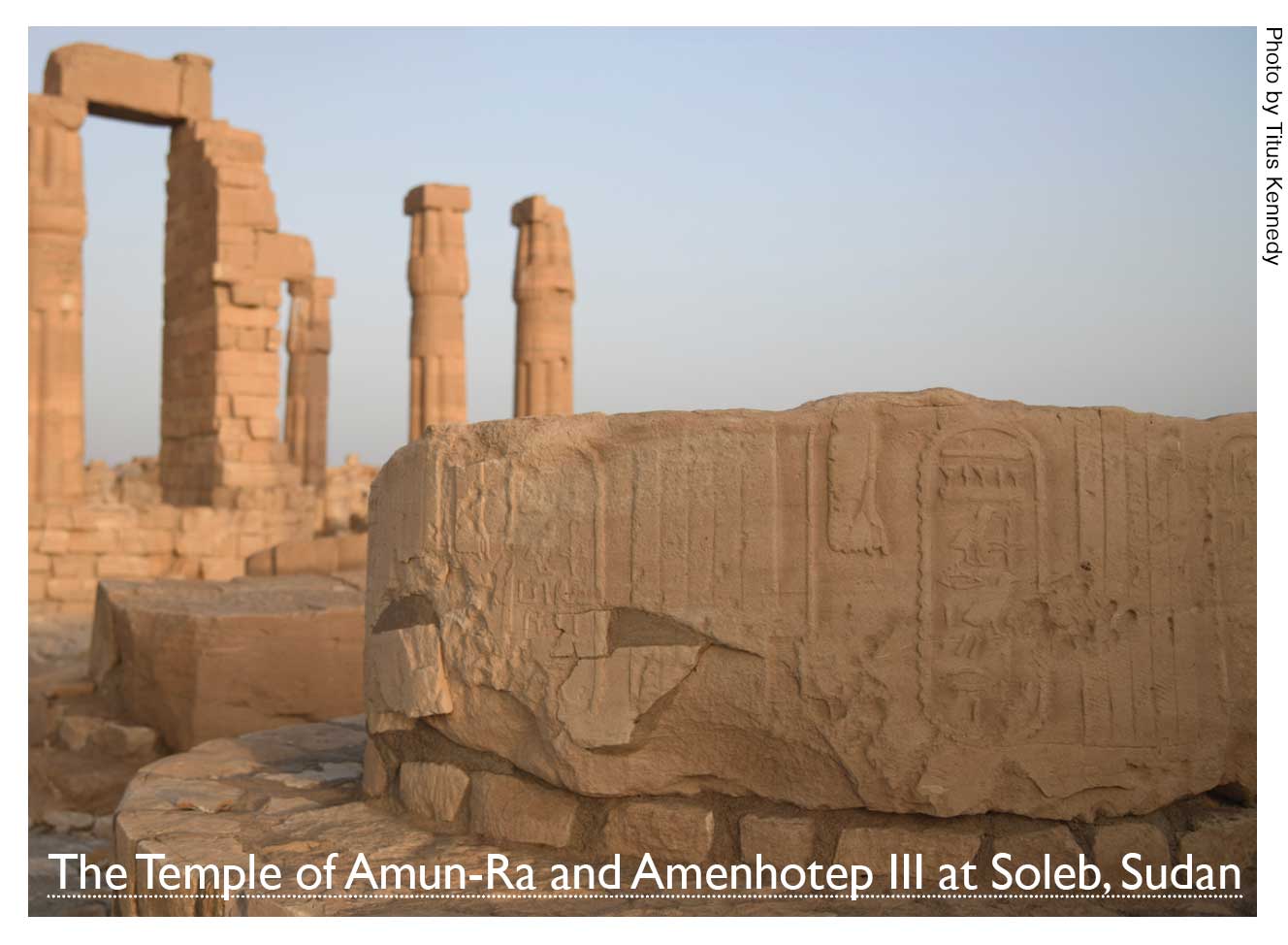

The Temple of Soleb

While nomads from millennia ago usually leave virtually no archaeologically discernible trace of their existence beyond rare inscriptions or petroglyphs, tentatively identified burials, or scant remains of a campsite, hieroglyphic inscriptions discovered at an Egyptian temple mentioning the “nomads of YHWH” (Yahweh) appear to attest to the Israelites’ presence in the Sinai and Transjordan areas east of Egypt, while also demonstrating that the Pharaoh was aware of the personal name of the Israelites’ God, which had been revealed to Moses only a few decades prior.6 These inscriptions appear to fill in an archaeological blank spot, and the discovery has significant implications for the historical reliability of the biblical narratives regarding the Exodus and wilderness wandering.

The story of these Egyptian inscriptions begins in 1813 when the explorer John Lewis Burckhardt identified the ruins of a temple at Soleb along the west bank of the Nile River in Kush or Nubia (present-day Sudan). The temple had been built during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty.7 Excavations were eventually carried out in 1957–1963, during which time the inscriptions were recorded and subsequently published.8

Excavations and investigations at the Soleb temple yielded numerous inscriptions about locations that were known to the Egyptians around 1400 BC and peoples who had allegedly been subjugated or dominated by the pharaoh by that time. Among the inscriptions noting various foreign nomads was a hieroglyph found on a section of a column transcribed as tA shasu yhwA, which translates to “land of the nomads of Yahweh.”9 Excavators also discovered a stone block from an interior wall bearing virtually the same inscription, “land of the nomads of Yahweh,” identical in word order and meaning to the relief on the column.

Inscriptions on the column named four different nomad groups. Geographically, these groups were located to the immediate east of Egypt, either in one of the wilderness areas or in Canaan.10 Decorations on the column depicted four bound prisoners, each of whom was designated as a nomad and was associated with a specific name. Although the names have been suggested as geographic locations, they cannot be linguistically connected to any currently known geographic names, and at least three of them appear to be deity names.11 One includes the deity Ba’al and the bull identified with him; another appears to mention the Canaanite goddess Anat; the third could be connected to the Shimeathites or a deity such as Setem or Shemat-Khu; and the fourth, on a cartouche on the column,12 mentions the nomads of Yahweh.13

“Yahweh the God of Israel”

The hieroglyphic signs for the Yahweh inscription are as follows:

N16 t3 (“land”)

M8 ša M23 sw G43 w = shasu (“nomads”)

M17 y O4 h V4 w3 G1 3 = yhw3 (“Yhwh”)

Correct identification and rendering of the hieroglyphic signs from these inscriptions are especially important because an error was introduced in the excavation report, and until recently, subsequent publications have followed the erroneous initial reading of “Yahu” (yhw), rather than “Yahweh” (yhwA).14 The mistake has enabled many scholars to assert that the inscription did not refer to Yahweh and was unrelated to the Israelites. However because the “land of the nomads of Yahweh” cannot be identified with any specific geographical place or the name of a person, the mention of Yahweh can most reasonably be understood as a reference to the divine name of God found in the Bible. Further, the four “nomads of X” phrases indicate that the Egyptians labeled nomad groups using the names of their associated deities, such that a nomadic people identified with the name Yahweh would have been worshippers of Yahweh.

While many scholars claim that Yahweh was not originally associated with the Israelites but was first worshipped in Edom as Qos or by the Canaanites in their pantheon, there is no evidence for any worship of Yahweh in ancient times outside of Israelite culture.15 Rather, all the earliest archaeological evidence associates Yahweh only with the Israelites. The exclusive association of the Israelites with Yahweh is also clear in biblical phrases, such as “Yahweh the God of Israel” and “Yahweh in the midst of this people [Israel].”16

The Right Time & Place

Another important aspect of the Soleb inscriptions is their date of composition, which can be determined using the date of construction and decoration of the temple on which they were found. Dedicated to the god Amun-Ra and commissioned by Pharaoh Amenhotep III, this temple would have been finished no later than year 29 of Amenhotep III (ca. 1385 BC). However, the temple was probably built slightly earlier, as indicated by the mention of year 26 on the decoration and pillars related to the Amenhotep III year five campaign to Kush.

While the claims of Pharoah defeating and subjugating many of these peoples, including the “nomads of Yahweh,” were probably propaganda, a logical timeframe for the names and toponyms recorded at the Soleb temple would be after the Kush campaign of year five, or about 1409–1385 BC. The earlier range, prior to 1400 BC and closer to the campaign, is more probable because the lists at Soleb function as a commemorative monument for the subjugation of Kush. This places the Egyptian mention of the “nomads of Yahweh” around 1400 BC, which agrees with the biblical wilderness-wandering chronology.

These inscriptions from Soleb are the earliest inscriptions mentioning Yahweh that have ever been discovered. They predate the mentions of Yahweh on the Amara West list by over a century and on the Moabite Stone of King Mesha by more than 500 years, but they coincide well with the time period of Moses.17

Based on the geographical locations listed at the Soleb temple, the area in which the Egyptians placed the “nomads of Yahweh” would have been around the regions of Sinai, Edom, Moab, Transjordan, or Canaan. According to the biblical records of the Israelite wandering, this would be precisely the region in which the Israelites lived as nomads following the Exodus.18 Old Testament narratives describe the Israelites during this period in various terms, such as “the people of Yahweh,” “Israel whom Yahweh made to wander,” and “the sons of Israel wandering aimlessly in the land.”19 Thus, the biblical details regarding names, times, and geographical locations match what the archaeological findings reveal about the Yahweh-worshipping Israelites wandering as nomads east of Egypt.

History, Not Myth

Taken together, the uniqueness of the name Yahweh, its identification as the name of a deity, and its association with a nomadic people east of Egypt all suggest that the Soleb inscriptions point to Egyptian recognition of “Yahweh,” the personal name of God, who was worshipped by the ancient Israelites. Since the Hebrews or Israelites were the only people in ancient times known to have worshipped a deity named Yahweh, it follows that these nomads associated with Yahweh can be identified with the early Israelites in their wandering period before they settled in Canaan.

Indeed, the Israelites did have a stormy relationship with Egypt, but to assert that the wilderness wandering was a myth conflicts with the archaeological data. The Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions at Soleb not only attest to the Israelites’ wandering period in the wilderness east of Egypt, but they also provide evidence that the Egyptians, including Pharaoh himself, were familiar with the Israelites around the time of the Exodus and knew the name of their God Yahweh at the end of the 15th century BC.

Notes

1. Herzog, Zeev, “Deconstructing the walls of Jericho,” Ha’aretz. 1999.

2. Redford, Donald, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, 260-261 (1992).

3. Finkelstein, Israel, “The Wilderness Narrative and Itineraries and the Evolution of the Exodus Tradition,” Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective, 49 (2015).

4. 1 Kings 6:1; Judges 11:26; Numbers 10:11-12, 14:33-34; Joshua 14:7-10.

5. Hasel, Michael, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 296 (1994).

6. Exodus 3:1-19.

7. Burckhardt, Travels in Nubia. (1819).

8. Schiff-Giorgini, Michela et al. Soleb I-V; Leclant, Jean, “Les Fouilles de Soleb (Nubie Soudanaise).”

9. Leclant, Jean, “Le tetragrame a l’epoque d’Amenophis III,” Near Eastern Studies (1991).

10. Levy, Adams, and Muniz, “Archaeology and the Shasu Nomads: Recent Excavations in the Jabal Hamrat Fidan, Jordan,” Academia.

11. Kennedy, Titus, “Nomads of Yahweh, the Exodus Wanderings, and the Soleb Temple,” Bible and Spade 34:2 (2021).

12. A cartouche is an oval ring surrounding hieroglyphs representing an important name.

13. Ba’al (Numbers 22:41; Judges 2:13); Anat (Joshua 15:59, 19:38; Judges 1:33, 5:6); Shimeathites (1 Chronicles 2:55; cf. 2 Chronicles 24:26).

14. Kennedy, Titus, “The Land of the š3sw (Nomads) of yhw3 at Soleb,” Dotawo A Journal of Nubian Studies (2019).

15. Kelley, Justin, “Toward a new synthesis of the god of Edom and Yahweh,” Antiguo Oriente Vol. 7 (2009).

16. Exodus 5:1; Numbers 14:14.

17. Exodus 3:13-16.

18. Exodus 19:1-2; Numbers 20:14-23, 22:1-4; Joshua 24:6-13.

19. Numbers 16:41, 32:13; Exodus 14:3; cf. Judges 5:9-13.

Titus Kennedy, PhD, is a field archaeologist who has been involved in excavations and survey projects at several archaeological sites in biblical lands, including directing and supervising multiple projects spanning the Bronze Age through the Byzantine period, and he has conducted artifact research at museums and collections around the world. He is a research fellow at the Discovery Institute, an adjunct professor at Biola University, and has been a consultant, writer, and guide for history and archaeology documentaries and curricula. He also publishes articles and books in the field of biblical archaeology and history, including Unearthing the Bible, Excavating the Evidence for Jesus, and The Essential Archaeological Guide to Bible Lands.

Get Salvo in your inbox! This article originally appeared in Salvo, Issue #68, Spring 2024 Copyright © 2025 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/article/salvo68/the-wanderers