Reflections on Real Life and Reasons for Living It

“I don’t want comfort. I want God. I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness, I want sin.” ~ John the Savage (Brave New World)

IRL is shorthand for “in real life” and is frequently used by Gen Zers and digital natives, who can’t remember a time without access to computers or the internet. But how is living life on this side of the Digital Revolution forming us?

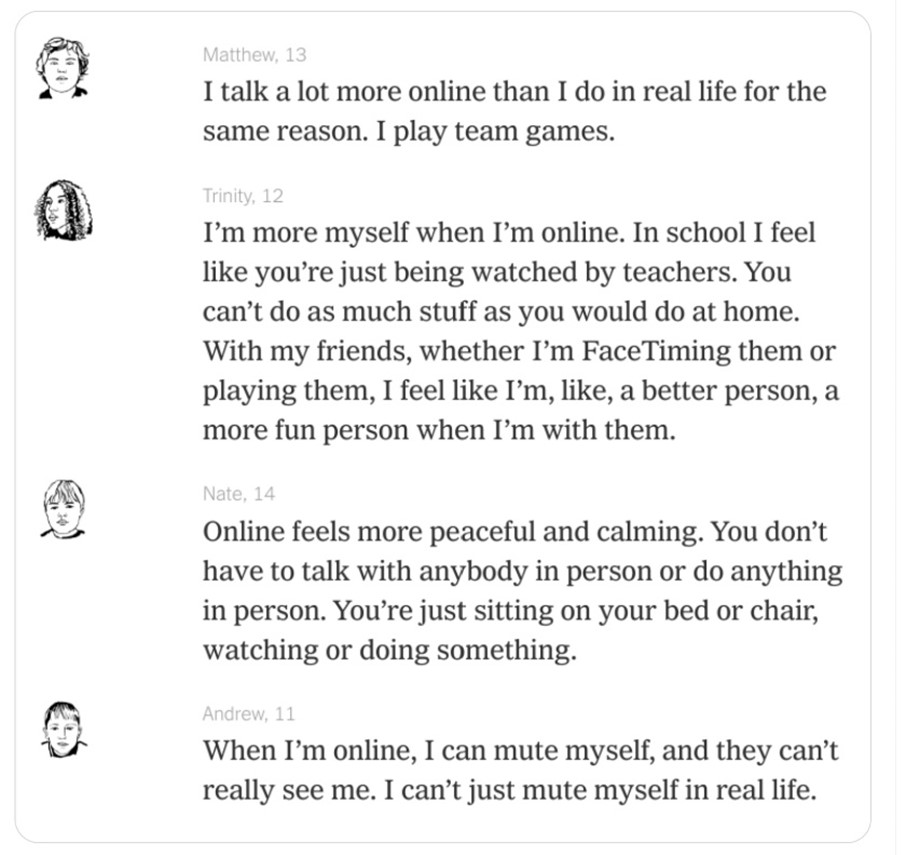

A recent New York Times focus group with teens offers some answers. Here’s what some of the teens said:

The Digital Revolution shapes us all. At any age, it’s easy to prefer a mediated, controlled experience of other people over the real thing, which inherently brings more unknowns and risks. Consider how easily we resort to text messages, emails, or DMs, rather than phone calls or in-person conversations. The technological cocktail of control and convenience make for an alluring elixir.

Yet for those who grew up before the Information Age, there is at least some reservoir of real-life experience to temper the drive towards digitalization. Not so for digital natives. Which makes it even more essential that we offer both compelling reasons and robust experiences that reveal online life as the flat shadow that it is: a numbed existence that pales in comparison to the dimension and depth of real-life experiences with each other and the world.

Soma-Numbed Existence

Freddie de Boer, who transcends tidy Right-Left categorizations, wrote an excellent reflection sparked by the Times’ teen focus group. He writes:

Here you have kids talking about why they prefer online life and identifying precisely the conditions that make me despondent: they like being online more than living their real lives because their online lives serve as an intermediary and distraction from what they don’t like about themselves and their world. They’re too young to know that you’re not supposed to admit that the point of being very online is to avoid the self. They say the quiet part out loud. Online life is more ‘peaceful and calming’ because online you’re permitted to be a vegetable. Online you can mute yourself, render yourself an unperson, remove yourself from existence and in so doing avoid the pain of being alive.

But, as de Boer points out, this is not the children’s fault per se. The problems are much bigger. Parents, teachers, and adult authority figures must provide structures for young people to learn how to live in real life and to come to appreciate its corrugations and textures. This means not sitting them in front of screens at school and at home. He explains:

The attitudes here are indicative of young people who have been failed by the adults around them, who in addition to the responsibility to keep them alive should be forcing them to contend with the inevitability of sadness and the need to come to terms with themselves. Someone has to tell these kids, “wherever you go, you’ll find yourself there, and you have to start to do the work of accepting who you are, as much as you may not like yourself.”

Another major factor showing that this is more than a “kids these days” problem is social media’s intentionally addictive design. The fourteen-year-old doesn’t stand a fighting chance against Silicon Valley designers who are racing to the bottom of our brain stems. Adults don’t stand much of a chance either. More from de Boer:

Some of the most well-resourced and brightest tech workers in our economy have the specific and exclusive task of ensuring that people have an unhealthy addiction to social media. This is why products like cigarettes are heavily regulated by the government; the potential for addiction undermines free choice and makes sensible use far more difficult. I don’t know or care if these apps are literally addictive in the same sense as various drugs. What I do know and care about is that many people have a deeply unhealthy relationship with them, use them to avoid real life, and feel that they can’t stop.

I can’t help but think of the soul-crushing, soma-induced existence depicted in Brave New World. In Huxley’s novel, soma is a drug that is freely available to everyone in multiple forms: powder, pill, and aerosol. Soma makes users feel happy, but also makes them complacent. It’s a form of escape that deadens them to the possibility of anything beyond recurring jolts of pleasure. And the Brave New World government is more than happy keeping the people happy—by keeping the doses coming. For their part, the people remain subservient and soft.

The internet and social media are our soma. Always available, freely distributed, with multiple methods of delivery. But there is another lesson in Brave New World from John the Savage, who boldly claims his “right to be unhappy.”

Risk-Filled Exhilaration

What can be done to help us all avoid the soma-like temptations of the internet age? How might we help kids like Matthew, Trinity, Nate, and Andrew, who find online life better than real life?

Enter John the Savage. Amid a soma-numbed world, John is the only remaining person born naturally from a mother and shaped by the world outside the control of the World State. While John has his own share of demons to reckon with, he wants something more than what the World State offers – something which brings exhilaration and conviviality, and with it risk and precarity. Everything crystalizes in John’s exchange with World Controller Mustapha Mond, where John says,

“But I like the inconveniences.”

“We don’t,” said the Controller. “We prefer to do things comfortably.”

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.”

“In fact,” said Mustapha Mond, “you’re claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“All right then,” said the Savage defiantly, “I’m claiming the right to be unhappy.”

“Not to mention the right to grow old and ugly and impotent; the right to have syphilis and cancer; the right to have too little to eat; the right to be lousy; the right to live in constant apprehension of what may happen tomorrow; the right to catch typhoid; the right to be tortured by unspeakable pains of every kind.” There was a long silence.

“I claim them all,” said the Savage at last.

Mustapha Mond shrugged his shoulders. “You’re welcome,” he said.

Rod Dreher explores this in Live Not by Lies, as well as here, where he writes:

How do you convince people to fight for their right to be unhappy? Can you imagine a task so difficult? It’s easier to convince people for their right to be free. But how do you make them understand that true freedom means the possibility of unhappiness, of suffering? No wonder people want to lose themselves in drugs and in obliterating their ability to pay attention. The burden of living in a world without meaning is too great. As the Savage intuits, we will either rediscover God, or we will be imprisoned in a dystopia of pleasurable lies.

de Boer concludes similarly. To those who are telling you “to give up on real love, real feeling, real people,” he implores,

I’m asking you to refuse. I’m asking you to choose the other thing, in whatever way you can. That’s the existential question for humanity in the 21st century. That’s the challenge in front of all of us. Will you shoulder the risk of pursuing real human connection, as hard and intimidating and discouraging as that can be? Or will you hide in your room forever, comforted by fast food and porn and opiates and therapy and TikTok, risking nothing? It’s up to you. I don’t pretend that it’s easy to choose the former. I don’t pretend that I always choose it or will always choose it, or that I’ve chosen it well, or that choosing it hasn’t cost me a great deal, at times. I know it’s not easy…. But to keep trying is to declare to the universe that you will have the courage to be human, when everyone and everything tempts you to be otherwise. Remember: you are you. We live here. This is now.

John the Savage was on to something, as are de Boer and Dreher. But, as Brave New World ends, John isn’t quite the hero. Instead, he commits suicide after a moral failing for which he can’t find forgiveness. There are a variety of interpretations to Huxley’s twist-of-an-ending, but my hunch is that part of it was, John was going it alone. The lone individual can’t withstand the forces of culture. John’s desire for truth and purpose was not situated within a larger community of fellow seekers with whom he could share failure and success. And that, I think, adds a dimension that frequently is forgotten in an individualistic society consumed with finding yourself. For real life to be worth it, there must be more than just remembering “you are you,” or fighting for “your right to be unhappy.” There must be a we; not just an I.

We must be grounded in flesh-and-blood human relationships, anchored to networks of giving and receiving from others, and oriented properly towards God who is both immanent and transcendent. There is no way around the challenges and difficulties of real life, but they are pregnant with meaning and possibility, too. It is in suffering and sacrifice alongside others that we are brought outside ourselves into a larger understanding of love, friendship, and human limits. And it is ultimately through suffering that God redeems the world.

“The Christian way,” Richard John Neuhaus explains, “is not one of avoidance but of participation in the suffering of Christ, which encompasses not only our suffering, but the suffering of the whole world.” Towards that end, how much better when we can say, “We claim the right to be unhappy. And, through such suffering and sacrifice, which Christ redeems, we find an ultimate and lasting source of happiness and joy—together.”

Further Reading:

- Peter Biles – “A Transhumanist Nightmare”

- Sherry Turkle - "Relational Artifacts From Virtual Pets to Digital Dolls"

- Joshua Pauling - "Virtual Children, Real Problems"

- Robin Phillips - "The New Couplings: Are Human & Robot Weddings Next?"

is a classical educator, furniture-maker, and vicar at All Saints Lutheran Church (LCMS) in Charlotte, North Carolina. He also taught high school history for thirteen years and studied at Messiah College, Reformed Theological Seminary, and Winthrop University. In addition to Salvo, Josh has written for Areo, FORMA, Front Porch Republic, Mere Orthodoxy, Public Discourse, Quillette, The Imaginative Conservative, Touchstone, and is a frequent guest on Issues, Etc. Radio Show/Podcast.

• Get SALVO blog posts in your inbox! Copyright © 2025 Salvo | www.salvomag.com https://salvomag.com/post/considering-john-the-savage